“Fist seen around the world”: The 1968 Olympics Protest – 50 years later

Sports and politics. The two worlds that have collided and some would say the recent protests and boycotts across the country and in various leagues…

Sports and politics. The two worlds that have collided and some would say the recent protests and boycotts across the country and in various leagues are the result of divided athletes and teams. However, athletes involved in politics is in fact not new at all. 50 years ago, two African – American sprinters, John Carlos and Tommie Smith, would lay the foundation of athletes protesting in Mexico City, Mexico during the 1968 Olympics with a silent gesture which would make tremendous volume in history.

1968 was a turbulent time in American History. It was by far the deadliest year of the Vietnam War, cities across America erupted in civil unrest after the assassination Civil Rights Leader Martin Luther King, Jr and Senator Robert F. Kennedy was also assassinated just two months later. With rebellion engulfing in North America and Europe against the wars, it seemed the ’68 Olympics would be a place of refuge, peace and unity as the best the athletes in world competed. Yet, unbeknownst to many in attendance and across the globe, it would be the epicenter of social change and the rise of the moral obligation of “The Black Athlete.”

Black Athletes began to be the voice of the unheard at the height of racial, social injustice and discrimination in the late 1960s. This started on the campus of San Jose State College (SJSC) by Dr. Harry Edwards, a former two-sport athlete now professor at SJSC. As a student, Edwards saw first- hand the inequality between black and white athletes. As a professor, he sought to bring together athletes of the same mindset. Among Edwards’ early disciples were the speedy duo of Smith & Carlos, along with teammate Lee Evans, who were students at SJSC. Edwards wanted to call attention to the discrimination and mistreatment felt by Black Americans, so he started an organization called the Olympic Project For Human Rights (OPHR). In the year leading up to the Olympics in 1967, the most notable and outspoken Black Athlete was the late great Heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali. After refusing to be drafted for the Vietnam war, Ali was stripped of his heavyweight title belt. Inspired by the actions of many influential athletes, Edwards wanted to bring national attention to the movement. His idea: a boycott of the 1968 Olympic games.

So it began slowly, but surely. In February 1968, Lew Alcindor [Kareem Abdul Jabbar] announced that he would not try-out for the Olympic team. “Someone that popular and that great of an athlete to take the risk to come with us and to put his career in jeopardy, I had great admiration” said Jim Brown. With the best player in collegiate basketball taking a stance, the OPHR had been given the attention they sought out. During the summer Olympic trials in California, while athletes wore pins & buttons in support of the OPHR movement, the idea of a boycott began to lose traction and instead focused on raising awareness because of a divisive front amongst other black athletes. There was also the issue of demands not being met, which included the dismissal of the International President Committee President Avery Brundage, who stood strongly against the boycott. In October, with the Mexico City Olympic Games fully underway, fans in attendance and many others across the globe cheered on their countrymen, but also may have wondered, would there be a protest.

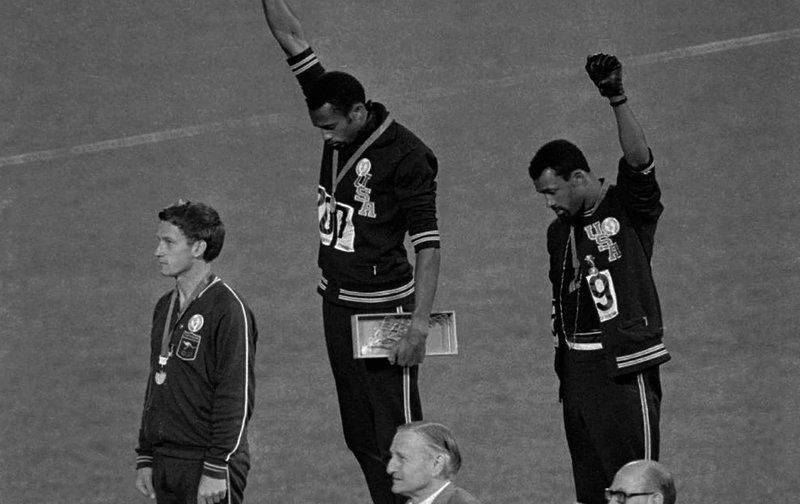

On October 16th, Tommie Smith and John Carlos were successful in the final 200-meter dash with Smith winning the gold medal and Carlos winning the bronze. Though both sprinters knew they were going to make a statement on the podium, they would be joined by an unlikely ally in Australian sprint Peter Norman, who won the silver medal. Norman, in solidarity with the sprinters, would wear an OPHR button he received from Paul Hoffman, a coach of the Harvard Rowing crew who were advocates of the athletes. With Norman on their side, Smith and Carlos had their own symbols with special significance. They wore black socks with no shoes to represent black poverty in America, Carlos wore his jacket unzipped to represent the working class people and beads around his neck symbolizing the history of lynching in America while Smith wore a Black scarf. Smith’s wife brought a pair of Black gloves. As “The Star Spangled Banner” began to play, with Smith wearing the right glove and Carlos wearing the left, both raised their fists with heads bowed in prayer. The raised fists formed together created an arch, representing black unity and power. In an interview, Smith went on to call it, “A cry for freedom.” Though they were sent home to America shortly, suspended from the US track team and even received death threats, the image would soon he around the world and has forever created a dialogue of Sports & Politics. In 2016, they were both invited back to a Team USA Awards Ceremony for the first since 1968.

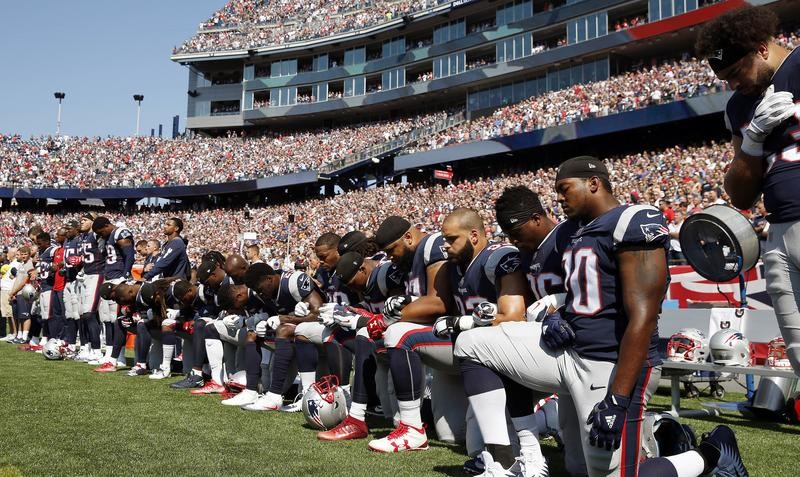

A half century ago, a flame was sparked in the Mexico City Olympic Games that would forever leave a burning trail in history. These Olympic Games began a paradigm shift with sports and politics. What two Black Sprinters had done for 80 seconds on the biggest sports stage will be remembered forever and has left them immortalized. Statues sit in both The African American Museum of History and Culture in Washington, D.C and on the campus of San Jose State where the movement began. They raised their fist in protest, paying the price for what they believed. Now, with athletes making political statements, it is deemed controversial in the eyes of many due to increase of financial accessibility of today’s athlete. Nonetheless, for every time a NBA player wears an “I can’t breathe” or a “More Than an Athlete” shirt, a NFL player kneels or any athlete takes a stand of social injustice, there is no doubt that they are paying homage to the legacy of John Carlos and Tommie Smith. It is also reminder to the status quo of what it means to be “Black in America” and the responsibilities of being a “Black Athlete in America.”

By: Jamal Clarke

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed by the authors and those providing comments, opinions on this website are theirs alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions or positions of M-Lifestyle and their affiliates. M-Lifestyle does not claim ownership of any images used, unless otherwise specified.

![]()