Unveiling Racial Disparities in America’s Housing Crisis Post-Pandemic

The housing crisis has been an ongoing issue in America since 2007. It has become painfully noticeable due to the COVID-19 pandemic and how the…

The housing crisis has been an ongoing issue in America since 2007. It has become painfully noticeable due to the COVID-19 pandemic and how the crisis affects people. Research has been done to understand the housing issues before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies show that racial and ethnic minorities seem to have more of a struggle with the inequality effects in housing than other communities. Though the housing crisis may not be racially motivated, it doesn’t shy away from the fact that racial and ethnic minorities have a burden from this issue.

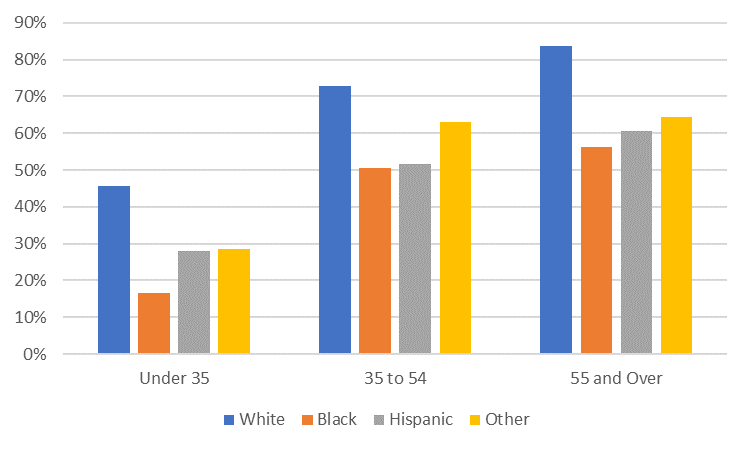

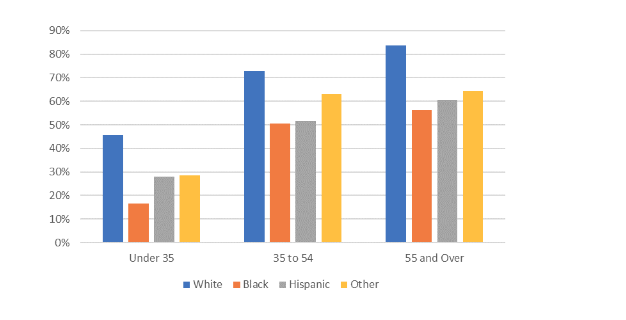

Source: Treasury calculations using data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a growth in America’s unemployment rate: it increased from 3.5% to 14.7% according to Yung Chun in his research. As a result, racial and ethnic minorities are burdened with economic effects such as housing hardships. Black and Hispanic households are more likely to experience these hardships, which can manifest in eviction as well as delays in mortgage, rent, and bill payments. Due to these struggles caused by the increase in the crisis, especially with poor housing stock, and lack of access to education and jobs, minority-dominant neighborhood residents were 66% more frequently evicted than other neighborhoods due to racial inequity. Those neighborhoods tend to have poor housing stock and lack access to quality education and job opportunities; they also often live in racially/ethnically segregated neighborhoods.

Not only do the racial and ethnic inequalities affect housing, but they also reflect in other areas, such as access to liquid assets (checking accounts, money market accounts, savings, cash, and/or pre-paid cards) and stable, high-quality jobs. Due to these circumstances, members of these groups are limited from building wealth, transferring money, and maintaining other assets across generations. Worries about financial shock, then, add to the hardships these households have to worry about.

Financial shock, an unexpected disturbance that originates from the financial sector and has a significant effect on an economy, tends to increase housing hardships, especially for financially vulnerable households. Households with lower levels of savings and wealth may encounter increased risks of mortgage delinquency and foreclosure during economic shocks—this creates compound financial hardships. These communities are then vulnerable to economic instability through having less wealth, overrepresented low wages, less secure, and precarious jobs, which means the communities are exposed to spiraling unemployment rates.

Yung Chun, research assistant professor at Washington University in St. Louis and the lead of Social Policy Institute, did five studies which were done on White, Asian, Black, and Hispanic U.S. residents where they took a survey on their housing hardships, income, liquid assets amount within the last 3 months, and employment shock during the pandemic. 71,800 adults entered the survey; however, due to failing to meet quota or failed quality checks, 22,939 were analyzed from all communities. This was done by a large online-panel provider distributed to all respondents.

These five studies showed that in August of 2020, 6.3% of respondents were forced to move by a landlord or bank, 11.1% were having difficulty keeping up with their mortgage/rent payments, and 14.4% skipped paying a utility bill or paying a bill late in the 3 months. Though these percentages decreased in 2021, the levels for each respondent were still higher than before the pandemic. The foreclosure upon homeowners was 0.4% in 2019 and the mortgage or rent delinquency rate in 2019 was 4.5%.

Racial/ethnic identity and income were still in play with the housing-related hardships during the pandemic. Families of minority groups were more vulnerable to housing-related hardship in the earlier stages of the pandemic than white families. Black respondents were 1.7 times likely to be forced to move, 1.9 times to be delinquent on housing payments, and 1.8 times to be delinquent on utility bill payments compared to white respondents in August 2020. Hispanic respondents were twice as likely to have had an eviction/foreclosure risk, and to have missed a housing payment, as well as 1.6 times to have missed paying a utility bill. Asian/other groups experienced fewer housing hardships than white respondents throughout the pandemic.

The second wave of surveys—taken in June of 2020—shows the gap between white and Black/Hispanic respondents widened and remained significant. 15.3% of white respondents experienced housing-related hardship between June and August of 2020 while 22.6% of Black and 21.9% of Hispanic respondents experienced housing instability. After June and August of 2020, housing inequality decreased. The decline was due to increased housing stability for Black and Hispanic households. However, white respondents’ experience with housing hardships increased insignificantly. The increase was larger than the relative decrease among Black and Hispanic households.

In the third wave—taken from November to December of 2020—the white respondents who experienced housing hardships increased by 4.0% while housing hardship decreased in Black and Asian/other respondents by 2.3-2.8%. However, Hispanic respondents slightly increased by 0.6%.

The fourth wave—taken from February to March of 2021—white respondent housing instability decreased by 4.3%. However, the housing instability gap narrowed in the final survey—taken in May of 2021. The proportion of Black and Hispanic respondents with housing hardships decreased by 4.9%.

The results show that respondents of color were immediately affected by the pandemic shock and recovered slowly. Hispanic respondents exhibited both a slow response to the pandemic shock and a slow recovery. While White respondents experienced lower rates and, though their housing hardships increased later, they recovered more quickly after their hardship rates peaked. Asians had a steady decline in hardships throughout the study period after their peak in the first wave.

The idea of this study is not to mean that the pandemic created inequalities in housing instability among minority groups. Inequalities have been present before the pandemic. Lack of access to government services may be a reason for their disproportionate hardship experiences; also, a lack of adequate information due to language barriers and discrimination at both institutional and individual levels. The study suggests that these mechanisms are contributing to housing instability during the pandemic varied between Black and Hispanic groups.

Though there are some recurring issues, the CARES Act has begun addressing the economic shocks and will be essential to helping these families.

This study highlighted potential long-lasting implications for inequality in the housing market during the pandemic. These communities have been struggling for years prior to the pandemic and have seen slight progress in the crisis; however, the Hispanic community is both slow to respond to the shock and recover after the pandemic. Racial and ethnic inequalities during the pandemic were interrogated while also exploring individual sets of association. Other findings are how important stable and adequate housing is, especially during a pandemic to maintain public health. Stay-at-home orders are a core component to the public health response to COVID-19 pandemic, but without housing, individuals/families cannot shelter in a place to prevent the spread of disease. To understand and combat housing hardship among vulnerable populations, it is, therefore, essential to a sound public response.

By: Rosie Bagay

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed by the authors and those providing comments, opinions on this website are theirs alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions or positions of M-Lifestyle and their affiliates. M-Lifestyle does not claim ownership of any images used, unless otherwise specified.

![]()